Representing entities and relations in an embedding space is a well-studied approach for machine learning on relational data. Existing approaches, however, primarily focus on improving accuracy and overlook other aspects such as robustness and interpretability. In this paper, we propose adversarial modifications for link prediction models: identifying the fact to add into or remove from the knowledge graph that changes the prediction for a target fact after the model is retrained. We introduce an efficient approach to estimate the effect of such modifications by approximating the change in the embeddings when the knowledge graph changes. We use these techniques to evaluate the robustness of link prediction models (by measuring sensitivity to additional facts), study interpretability through the facts most responsible for predictions (by identifying the most influential neighbors), and detect incorrect facts in the knowledge base.

CRIAGE: Completion Robustness and Interpretability via Adversarial Graph Edits

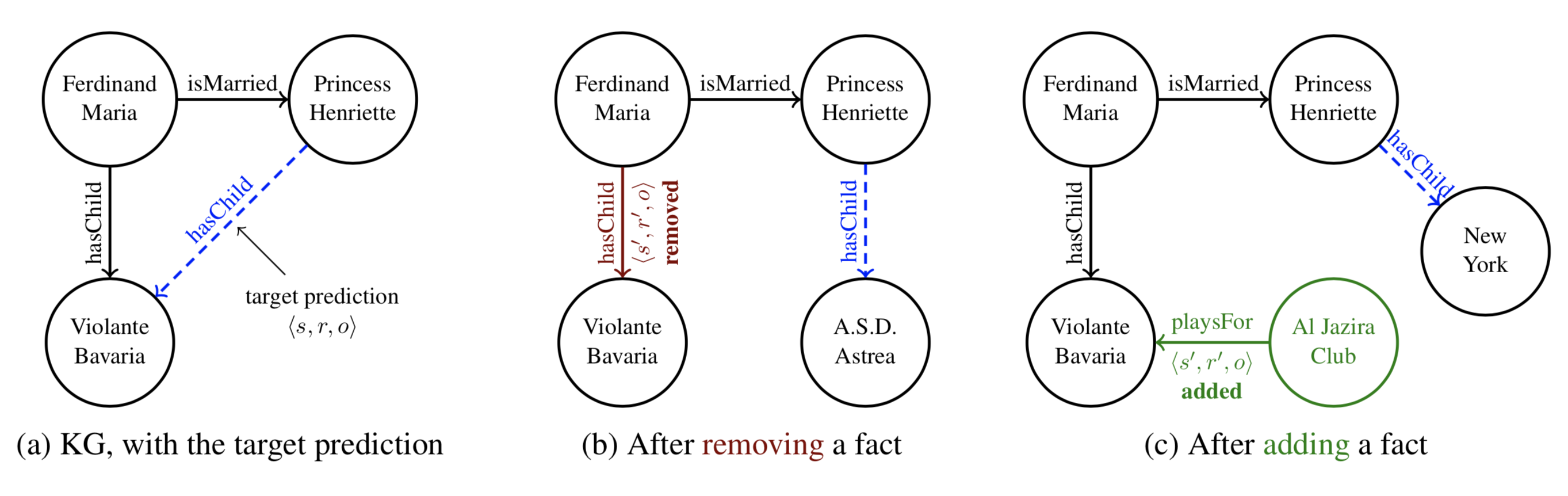

For adversarial modifications on KGs, we first define the space of possible modifications. For a target triple <s, r, o>, we constrain the possible triples that we can remove (or inject) to be in the form of <s', r', o> , i.e, s' and r' may be different from the target, but the object is not.

Removing a fact (CRIAGE-Remove)

For explaining a target prediction, we are interested in identifying the observed fact that has the most influence (according to the model) on the prediction. We define influence of an observed fact on the prediction as the change in the prediction score if the observed fact was not present when the embeddings were learned. Previous work have used this concept of influence similarly for several different tasks.

Formally, for the target triple <s,r,o> and observed graph G, we want to identify a neighboring triple <s',r',o> in G such that the score ψ(s,r,o) when trained on G and the score ψ'(s,r,o) when trained on G-<s',r',o> are maximally different, i.e.

Where ∆(s,r,o) =ψ(s,r,o)−ψ’(s,r,o).

Adding a new fact (CRIAGE-Add)

We are also interested in investigating the robustness of models, i.e., how sensitive are the predictions to small additions to the knowledge graph. Specifically, for a target prediction <s,r,o>, we are interested in identifying a single fake fact <s',r',o> that, when added to the knowledge graph G, changes the prediction score ψ(s,r,o) the most. Using ψ'(s,r,o) as the score after training on G ∪ <s',r',o>, we define the adversary as:

Where ∆(s,r,o) =ψ(s,r,o)−ψ’(s,r,o).

Efficiently Identifying the Modification

In this section, we propose algorithms to address mentioned challenges by (1) approximating the effect of changing the graph on a target prediction,and (2) using continuous optimization for the discrete search over potential modifications.

First-order Approximation of Influence

To capture the effect of an adversarial modification on the score of a target triple, we need to study the effect of the change on the vector representations of the target triple. As a result, using the Taylor expansion on the changes of the loss after conducting the attack, we approximate ψ(s,r,o)−ψ'(s,r,o) as:

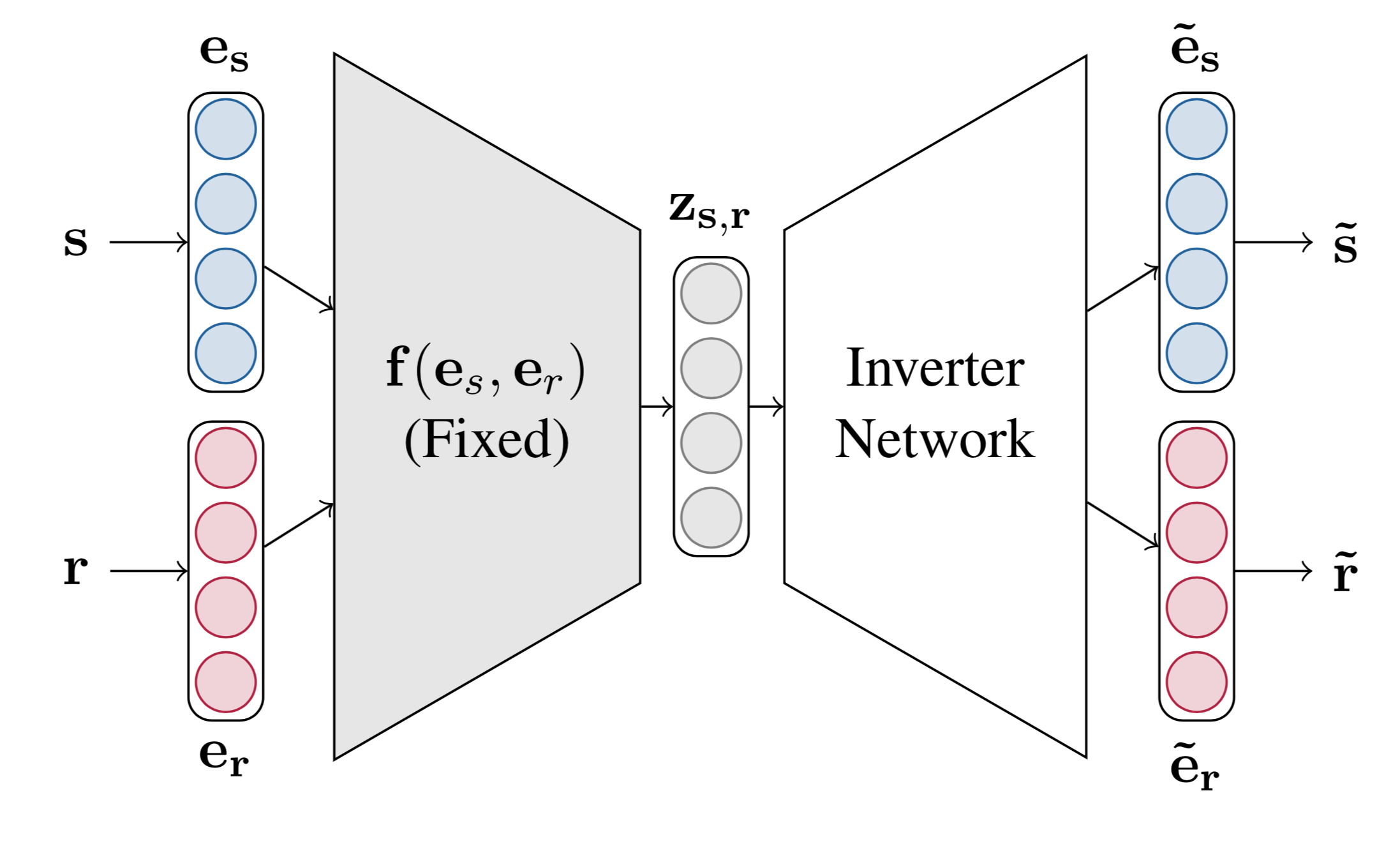

Continuous Optimization for Search

Using the approximations provided in the previous section, we can use brute force enumeration to find the adversary〈s′,r′,o〉. This approach is feasible when removing an observed triple since the search space of such modifications is usually small. On the other hand, finding the most influential unobserved facts to add requires search over a much larger space of all possible unobserved facts (that share the object). Instead, we identify the most influential unobserved fact〈s′,r′,o〉by using a gradient-based algorithm on vector Z(s',r') in the embedding space. After identifying the optimal Z(s′,r′), we map the vector Z(s′,r′) to the entity-relation space, i.e., translating it into (s′,r′) using above inverter network.

Experiments

We evaluate CRIAGE by, 1) comparing CRIAGE estimate with the actual effect of the attacks, 2) studying the effect of adversarial attacks on evaluation metrics, 3) exploring its application to the interpretability of KG representations, and 4) detecting incorrect triples.

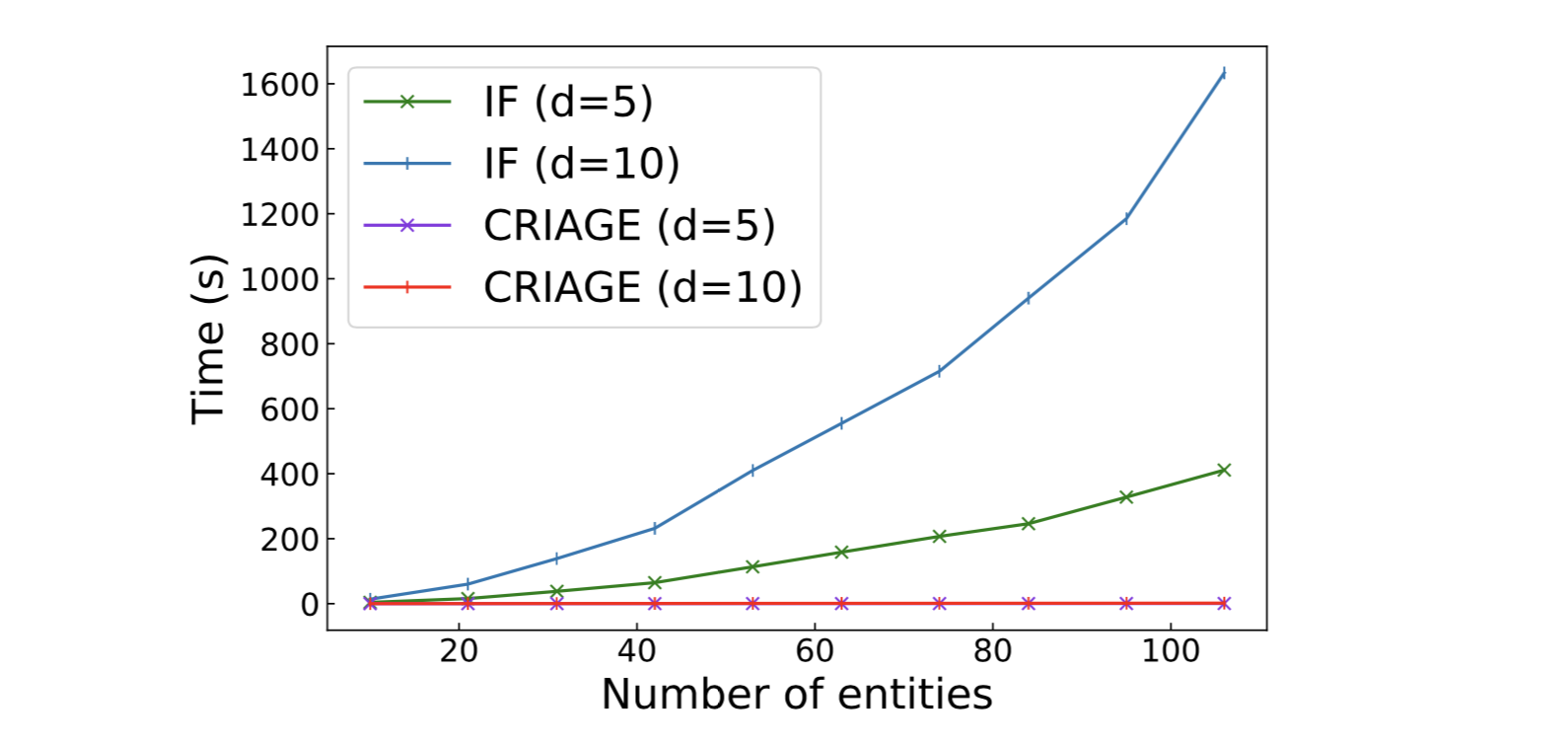

Influence Function vs CRIAGE

We show the time to compute a single adversary by IF (influence function) compared to CRIAGE, as we steadily grow the number of entities (randomly chosen subgraphs), averaged over 10 random triples. As it shows, CRIAGE is mostly unaffected by the number of entities while IF increases quadratically. Considering that real-world KGs have tens of thousands of times more entities, making IF unfeasible for them.

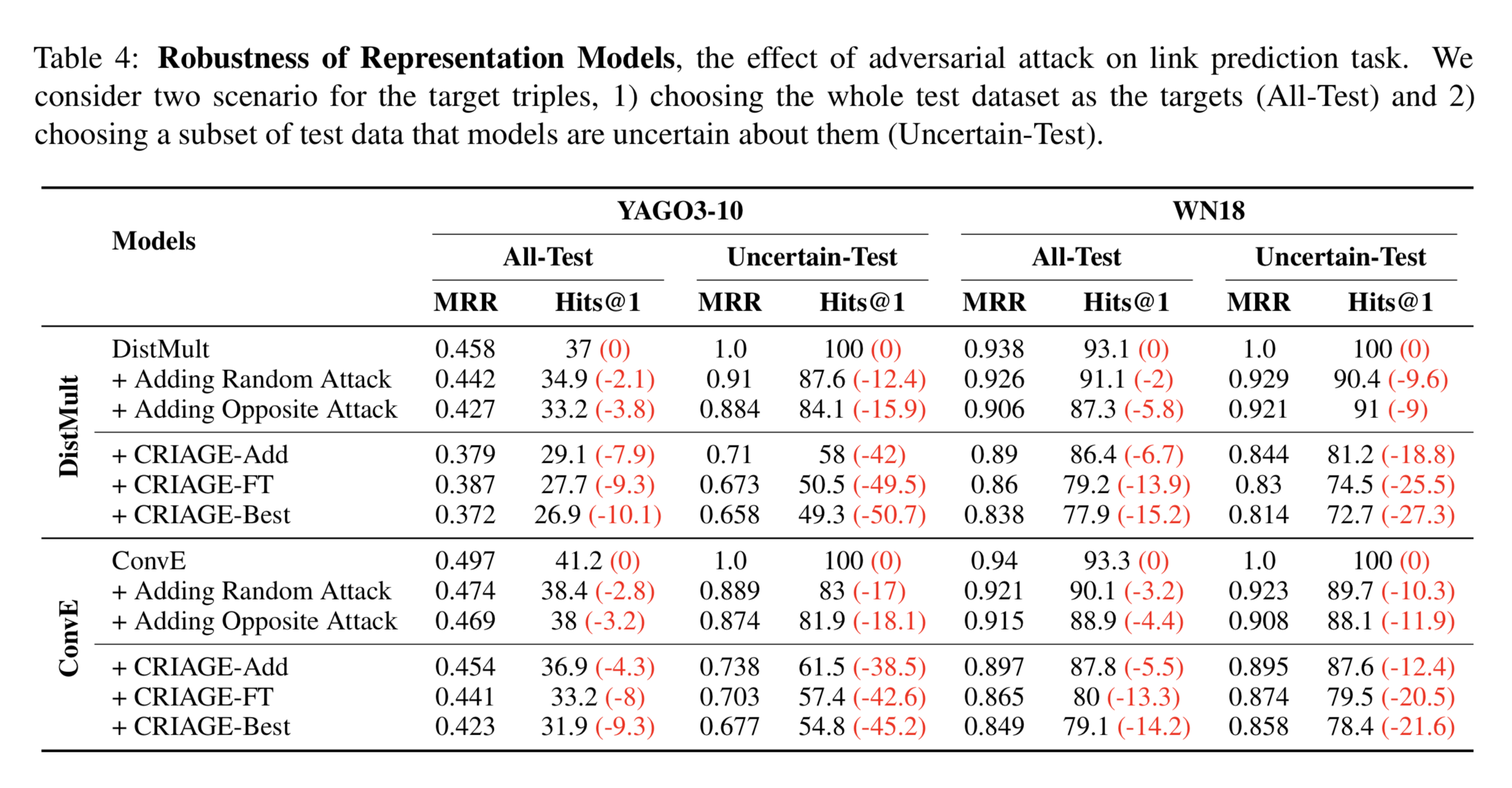

Robustness of Link Prediction Models

Now we evaluate the effectiveness of CRIAGE to successfully attack link prediction by adding false facts. Since this is the first work on adversarial attacks for link prediction, we introduce we consider two baselines to compare against our method: 1) choosing a random fake fact〈s′,r′,o〉(Random Attack); 2) finding (s′,r′) by first calculating f(e_s,e_r) and then feeding −f(e_s,e_r) to the decoder of the inverter function (Opposite Attack). In addition to CRIAGE-Add, we introduce two other alternatives of our method: (1) CRIAGE-FT, that uses CRIAGE to increase the score of a fake fact over, and (2) CRIAGE-Best that selects between CRIAGE-Add and CRIAGE-FT attacks.

All-Test: The result of the attack on all test facts as targets is provided in the Table 4. CRIAGE-Add outperforms the baselines, demonstrating its ability to effectively attack the KG representations. It seems DistMult is more robust against random attacks, while ConvE is more robust against designed attacks.

Uncertain-Test: we consider a subset of test triples that 1) the model predicts correctly, 2) difference between their scores and the negative sample with the highest score is minimum. The attacks are much more effective in this scenario, causing a considerable drop in the metrics. Further, in addition to CRIAGE significantly outperforming other baselines, they indicate that ConvE’s confidence is much more robust.

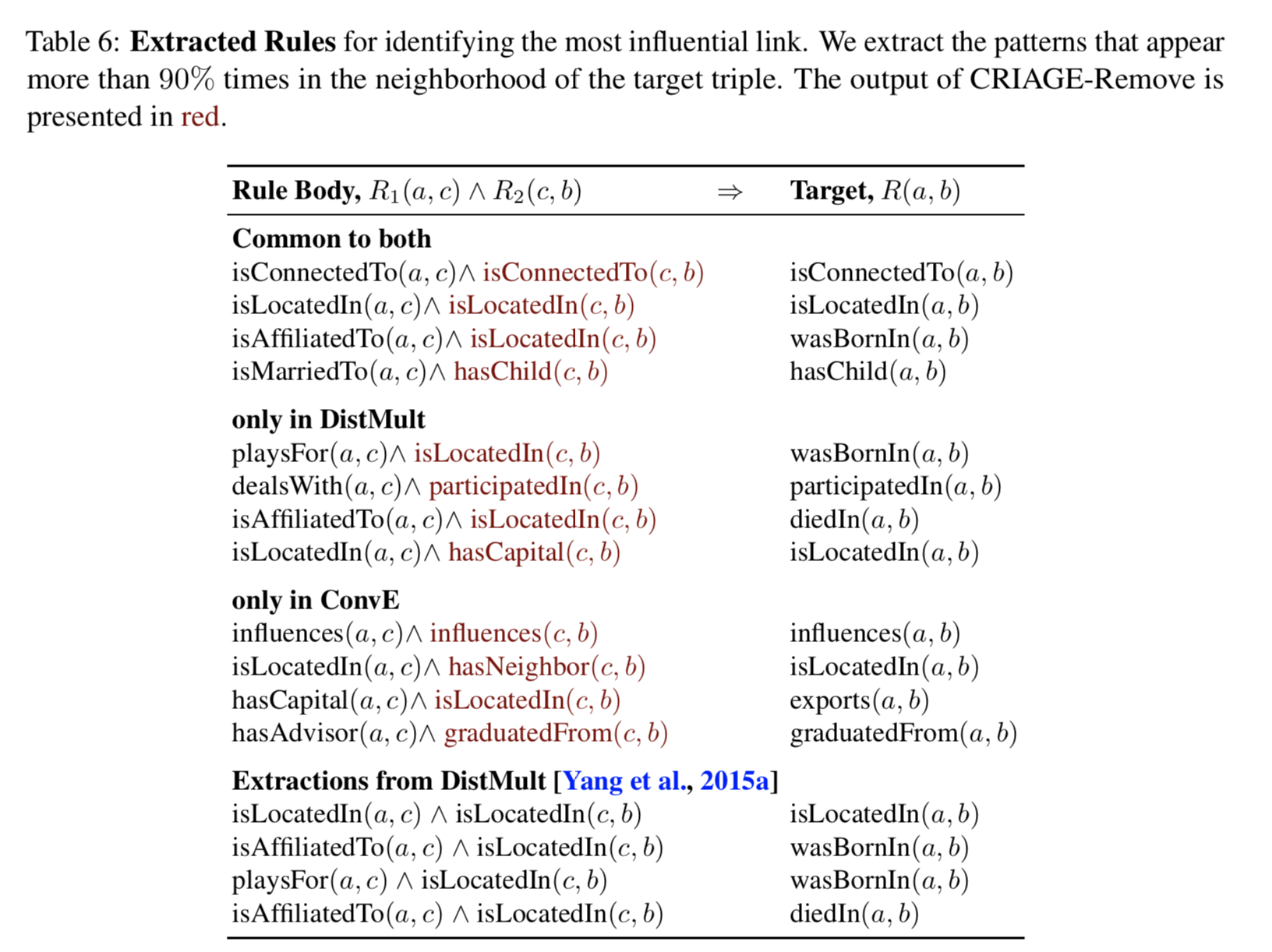

Interpretability of Models

To be able to understand and interpret why a link is predicted, we need to find out which part of the graph was most influential on the prediction. To provide such explanations, we identify the most influential fact using CRIAGE-Remove. Instead of focusing on individual predictions, we aggregate the explanations over the whole dataset for each relation using a simple rule extraction technique: we find simple patterns on subgraphs that surround the target triple and the removed fact from CRIAGE-Remove, and appear more than 90% of the time. The rules show several interesting inferences, such that "hasChildis" often inferred via married parents, and "isLocatedIn" via transitivity. Furthermore, DistMult often uses the "hasCapitalas" an intermediate step for "isLocatedIn", while ConvE incorrectly uses "isNeighbor". We also compare against rules extracted in DistMult paper. Interestingly, the extracted rules contain all the rules provided by CRIAGE, demonstrating that CRIAGE can be used to accurately interpret models.